In a conversation with C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien said, “We have come from God, and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God.” Within our legends and myths, there is a certain amount of truth. The same is true with what I would like to share today—a combination of facts, myths, and legends, and it all begins in the year 43 B.C. We can read about it in the Acts of the Apostles.

“Herod the king laid violent hands on some who belonged to the church. He killed James the brother of John with the sword, and when he saw that it pleased the Jews, he proceeded to arrest Peter also.” (Acts 12:1-3a) The Apostle James, brother of John and son of Zebedee, was martyred by beheading. It is from there that our legend begins.

Following his death, his followers, wanting to provide a proper burial for him but also wanting his body to be kept safe, took it to the coast, where they boarded a stone boat. The boat had no rudder or sail but was guided by an angel, which took it on a long journey across the Mediterranean, through the Strait of Gibraltar, and up to the northwest corner of Spain.

At this same time, a father was throwing a huge wedding party for his son. There was food, drinks, dancing, and games. One of the games played was abofardar—the men, riding horses, would take a spear and hurl it into the air as high and far as they could, then, charging forward, they would attempt to catch the spear before it hit the ground—very safe. The groom’s turn came, and he gave the spear a mighty throw. However, he was so focused on the spear that he paid little attention to where his horse was going, and he plummeted into the sea and disappeared. There was high tension as the crowd watched and waited for him to surface. Finally, he did. A way out from shore, the groom and horse popped up. Fortunately for them, there was a boat directly beside them. It was the stone boat carrying the body of the Apostle James.

After rescuing the groom and the horse, it was discovered that they were both covered in scallop shells. The followers of James on the boat saw this as a miracle, so the scallop shell became a symbol of all who were saved by coming to St. James.

Following these events, the body of St. James was secretly buried and essentially lost for almost 800 years until a hermit, Pelayo, noticed strange lights in the sky. Following the lights, Pelayo came to a field where he discovered the hidden tomb. He informed his Bishop, who, with several others, went to investigate and were able to determine that it was, in fact, the remains of the Apostle. A church was built over the tomb, and later a cathedral. The city that grew up around it that supported the pilgrims who came to venerate the saint was named Santiago de Compostella. Santiago is translated as St. James, and Compostella means “field of lights.” For the last 1,200 years, saints and sinners, lay people and clerics, rich and poor, popes and kings, have made the pilgrimage to pray before the remains of St. James the Great—one who was so very close and dear to Jesus.

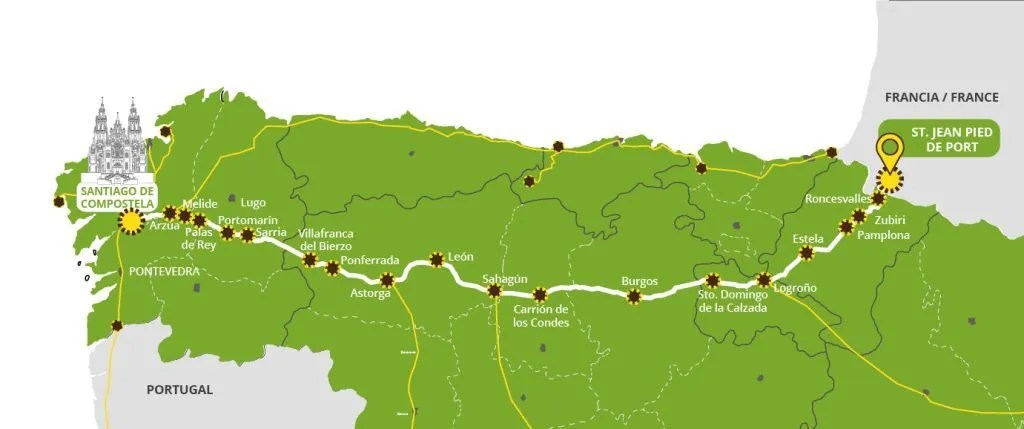

The pilgrimage is called the Camino de Santiago, the Way of St. James, and the starting point for many is Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, which means St. John at the Foot of the Pass—the pass is the one that takes you over the Pyrenees Mountains, from France into Spain. On April 10th of this year, I will rename this town Jean-Pied-de-Port—John at the Foot of the Pass (unless, of course, I’m sainted in the next month, then I’ll keep it the same.) The French Way, the route I will be taking, is the most popular and the one pilgrims have walked for 1,200 years.

I’ll take more time and make more stops, but there are traditionally 31 stops along the way, and early on, pilgrims would make the journey there and back, so with the Cathedral counting as their destination, you would have 63 stops. As they did not have the benefit of GPS and a well-marked trail, early pilgrims relied on various maps, one of which was created by the Templars. That early map has evolved into a game still played today (and one our kids will have the opportunity to play while I’m away)—The Royal Game of the Goose. Thus enter Albert the Goose. Why a goose?

It was the Templars who were charged with protecting pilgrims as they made the pilgrimage, and so it was the Templars who made the original map. Looking at our game board, you will see many of the squares have symbols in them. The meaning of most of the symbols is lost. Still, the labyrinth could represent physical and spiritual growth, a well might represent a lousy day, and a bridge—although it may be a specific bridge—can also represent a spiritual crossing. And then there is the goose. For the Templars, the goose represented wisdom, and throughout the Camino, if you keep your eyes open, you will see a goose carved in the base of a statue or a distinctive goose track in various locations. There are also towns with “Goose” in their names: Villafranca de Montes de Oca, Castrojeriz (city of geese), El Ganso, Ocón, Puerto de Oca, Manjarín (man of geese). (Source) While I’m away, Albert will also be traveling, and you may find him at your front door looking for a place to rest.

In the very early days of the Camino, there were tens of thousands of pilgrims, but the numbers waned due to wars and other issues. Eventually, it nearly fell out of use, and in 1979, only twelve people completed the walk. However, popularity has increased dramatically. Last year, which was considered a holy year, over 442,000 individuals walked a Camino.

To officially walk a Camino, you must walk at least 100km (62 miles). From St-Jean, where I’ll start, it is 800km (500 miles), and last year, of the 442,000, about 23,000 made that distance. For each, regardless of the distance, the shell—like the one attached to the groom and his horse—has become the symbol of the Camino de Santiago. It is what designates a pilgrim—they attach one to their pack or hat—and it is what marks The Way, with signposts, wayfaring markers, and various marks in the road.

Finally, the Camino de Santiago is a physical exercise—putting one foot in front of the other for 500 miles—but more than that, it is a spiritual exercise. It is a journey of the soul. It is a way of letting go of all except the most necessary and, hopefully, along The Way, discovering that all you truly need is God and a few items you can carry on your back. As I walk, I hope to declutter my mind and my soul, and just as I might leave some gear that I don’t use along the way, I hope to leave the clutter and discover that life is far simpler than we make it.

I will be on the Camino for 60 days, and I’ll be out for fourteen weeks. I will be very out of touch, but I will pray for you every day. As I’ve told several people, St. Matthew’s was around for 125 years before I got here, so I know you’ll be just fine and in very capable hands. I encourage you to participate in the events and activities that have been planned. In the process, you might just discover the spirit of the Camino and find The Way opening up before you.

Let us pray (this is the traditional pilgrim’s prayer that was written in the 12th century):

O God, who brought your servant Abraham

out of the land of the Chaldeans,

protecting him in his wanderings,

who guided the Hebrew people across the desert,

we ask that you watch over us, your servants,

as we walk in the love of your name.

Be for us our companion on the walk,

Our guide at the crossroads,

Our breath in our weariness,

Our protection in danger,

Our refuge on the Camino,

Our shade in the heat,

Our light in the darkness,

Our consolation in our discouragements,

And our strength in our intentions.

So that with your guidance we may arrive safe and sound

at the end of the Road

and enriched with grace and virtue

we return safely to our homes filled with joy.

In the name of Jesus Christ our Lord, Amen.

St. James the Greater, pray for us.

Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us.

Buen Camino!