Some of the old-timey Gospel music can be fun to listen to. Dr. Ruby Holland sang,

“Get back Satan, I’m running late

Get back Satan, I’m running late

Well I’ve got to get to Heaven, before they close the gate

Get back Satan, I’m running late.”

And Bishop Neal Roberson pleaded,

“Don’t let the devil ride,

Don’t let the devil ride,

Oh if you let him ride, he’ll want to drive…

Please Don’t let him drive your car…

Don’t do it, Don’t do it, Don’t do it!”

A simple theology—Jesus never complicated the message! That’s one of the wonderful things about musicians, artists, writers, and poets using their talents to express God’s truths. However, there are some—much like theologians—who go even deeper, creating works that require great skill and intellect to understand. Today, especially, I’m thinking about Dante Alighieri.

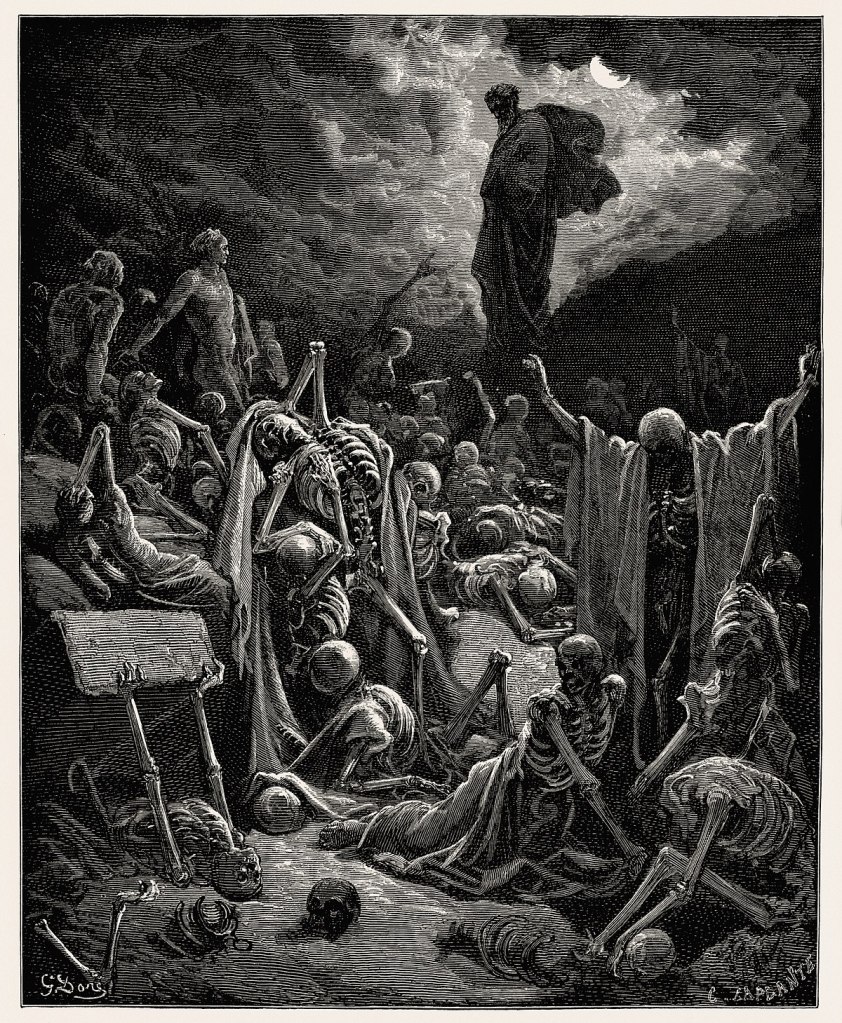

Dante wrote the epic poem The Divine Comedy, which consists of three major parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso (Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise). I’ll be honest and tell you that I have attempted it, but have not yet made it far. My sister-in-law recommended a translation to me, and it is on the way, so I plan to try again. Keep you posted.

For the opening verse of the first part, Inferno, Dante wrote,

“Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.”

For Dante, who acts as both the narrator and poet, finding himself in the dark forest means he has found himself in a place of sin and spiritual confusion. While searching for a way out, he meets the poet Virgil, who will serve as his guide through the nine levels of the Inferno, hell.

The deeper the level, the more heinous the sin. Level one includes the unbaptized and virtuous pagans. Level six is guarded by demons and reserved for heretics. Level nine is the home of Satan, where he chews on the worst traitors, including Judas Iscariot and Brutus, as in, et tu Brute?

For many centuries, Christians held a vivid and imaginative view of hell, but as we became more “enlightened,” that understanding gave way to doubt and disbelief. Now, for many, hell is nothing more than a myth that we tell children to keep them in line on rainy days. The author of the book, The Hell There Is, which we recently discussed at our Saints Book Club, states, “What is more common today, at least among the faithful, is not the outright denial of hell but a kind of practical denial of it by concluding, contrary to Scripture, that very few, if any, go to hell.” (p.2-3) He explains that individuals come to this conclusion because they don’t believe a loving God would condemn anyone to eternal punishment. However, for the author, God is not the one condemning people; rather, they are choosing hell themselves. To demonstrate this, the author references the parable of Lazarus and the rich man (also known as Dives, the Latin word for rich or wealthy). So, how does the parable show the man choosing hell over being condemned to it?

To begin (and I’ll refer to the rich man as Dives), Dives was very well aware of Lazarus’ condition. Lazarus was not sitting at the city gates where he might have occasionally been seen by Dives; instead, Lazarus was sitting at the gates of Dives’ house. Dives would have seen Lazarus every single time he went outside, yet Dives chose to ignore him. Dives did nothing directly against Lazarus, but sin isn’t limited to actions. We pray in the confession, “Most merciful God, we confess that we have sinned against you in thought, word, and deed, by what we have done, and by what we have left undone.” Sins of commission are the wrongs we do, and sins of omission are the good we fail to do, even when we know we should act.

Countless times throughout the history of God’s people, even before the time of Jesus, God called on His people to care for the poor. For example, Deuteronomy 15:11 states, “There will always be poor people in the land. Therefore, I command you to be openhanded toward your fellow Israelites who are poor and needy in your land.”

Disobeying this command, Dives, fully aware of Lazarus’ needs, committed a great sin of omission. He was not compelled to ignore him but chose to. Dives did not choose the ways of God; he chose the ways of self and the devil, making a conscious decision to prefer hell over heaven. Further proof of this choosing is that once there, Dives’ attitude does not change.

In Hades and in torment, Dives looks up and sees Abraham and Lazarus in Paradise. He calls out, “Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus to dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue; for I am in agony in these flames.”

That is the same attitude he had toward Lazarus while he was alive. Lazarus is a non-person to him. He does not ask Abraham to send Lazarus down to where he is so that he can beg for forgiveness. No. Instead, Dives asks for Lazarus to be sent down to serve him. “Abraham, tell that wretch to run this little errand for me.” Neither does Dives ask if he might come up to Heaven so he might escape his torment. He is neither willing to confess nor ask for forgiveness for his sins, which demonstrates that, despite the torments he is currently experiencing, he is still happy with the choices he has made. It is one of those situations where your only regret is that you got caught. Dives chose his current state, and he would rather remain in hell than walk in the ways of God. Do people truly make such an insane choice?

You are familiar with Jesus’ words in John 3:16—“For God so loved the world, that He gave His only Son…,” and John 3:18 tells us, “Whoever believes in Him [Jesus] is not condemned, but whoever does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the only Son of God.” Then Jesus says something quite remarkable in verse 19, “And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil.” (John 3:19) “This is the judgment,” may also be translated as “This is the condemnation.” So, if we rephrase 3:19, we could say, “This is the condemnation: Jesus came into the world, and people chose the darkness—they chose hell—rather than Jesus, because they preferred their evil ways over the ways of God.”

Yes. The author of the book is correct in his assertions—God does not condemn a person to hell; they choose it. What makes this choice so woeful is that after death, there’s no second chance. When Dives asked for that cool drop of water, Abraham told him that he had received his reward while alive and ignored the needs of another person. Additionally, Abraham tells Dives, “Between you and us a great chasm has been fixed, so that those who might want to pass from here to you cannot do so, and no one can cross from there to us.” Death is not a threshold we cross. Death is a chasm that, once crossed, cannot be breached.

The author writes, “Think of wet clay on a potter’s wheel. If the clay is moist and still on the wheel, it can be shaped and reshaped, but once it is put in the kiln, in the fire, its shape is fixed forever. So it is with us that when we appear before God, who is a holy fire, our fundamental shape will be forever fixed, our decisions will be final. This is mysterious to us, and we only sense it vaguely, but because heaven and hell are eternal, it seems reasonable to conclude that this forever-fixed state is in our future.” (p.76)

With that understanding, I have some good news for you and I have some bad news for you. Let’s start with the bad news—“All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,” (Romans 3:23) and “the wages of sin is death.” (Romans 6:23) We have sinned and we are dead in our sin; therefore, we are already on the wrong and unbreachable side of the chasm. We are dead in our trespasses and sins because we too have not followed the ways of God. (Cf Ephesians 2:1-3) That’s the bad news. The Good News is this—like the clay on the potter’s wheel, we have not yet been placed in the kiln. Our final shape, our forever-fixed state, is not yet set. There is still time to make another choice—a better and eternal one—and that is what Jesus offers us all. Jesus has created the one and only way by which we can cross the unreachable chasm, and that Way is through Him. “Jesus said to him, ‘I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.’” (John 14:6)

“Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.”

Certain actions we take and choices we make can lead us into that same dark forest where we lose the straightforward pathway. If we persist, then, in the end, the consequences of those actions and choices bring us to that Inferno which is forever fixed. If, however, we choose the Way that Christ Jesus has established, then we are gifted an eternal dwelling place with God in the New Jerusalem. My advice then is this,

Don’t let the devil drive your car.

Don’t do it, Don’t do it, Don’t do it!

Let us pray: Loving Father, faith in Your Word is the way to wisdom. Help us to think about Your Divine Plan that we may grow in the truth. Open our eyes to Your deeds, our ears to the sound of Your call, so that our every act may help us share in the life of Jesus. Give us the grace to live the example of the love of Jesus, which we celebrate in the Eucharist and see in the Gospel. Form in us the likeness of Your Son and deepen His Life within us. Amen.