Boudreaux dies and arrives at the Gates of Heaven, where he sees a huge wall of clocks behind him.

He asks St. Peter, “What are all those clocks?”

St. Peter says, “Those are Lie Clocks. Everyone on Earth has a Lie Clock. Every time you lie, the hands on your clock will move.”

“Oh,” says Boudreaux, “whose clock is that?”

“That’s Jesus’ clock,” Peter answered. “It has never moved, showing that he never told a lie.”

“Incredible,” says Boudreaux. “And whose clock is that one?”

Peter responds, “That’s Abraham Lincoln’s clock. The hands have moved twice, telling us that Abe told only two lies in his entire life.”

“So where’s my clock?” asks Boudreaux.

“Your clock is in God’s office. He uses it as a ceiling fan.”

In his book Phaedrus, Plato wrote, “An alliance with a powerful person is never safe.” The same is true with alliances between nations. The history of Israel, during the time of the prophets, makes the point.

In 609 BC, Josiah was the King of Judah (The King of the South). At that time, the Egyptians were marching north for battle with another kingdom, but Josiah decided to attack them for unknown reasons. That did not go well, and Josiah was killed in battle. Judah then became a vassal of Egypt and had to pay them a handsome tribute. Josiah’s son, Jehoahaz, ascended the throne, but Egypt didn’t like him as king, fearing that he would seek vengeance for his father, so the Egyptians removed him and installed Jehoiakim as king.

That relationship was rocky but was working as planned until along came the Babylonians, who won a decisive victory against Egypt in 605 BC. Jehoiakim, wanting to save his own backside, switched his allegiance to Babylon and paid them tribute, including some of the holy items from the Temple. As you would imagine, this did not go over well with everyone, including Prophet Jeremiah.

Jeremiah had been close to Josiah, but he saw Jehoiakim as a wicked king—which he was—and denounced him.

Although strong, the Babylonians could not fully control the Egyptians and the surrounding area. In 597 BC, thinking that the Babylonians had been so weakened that he could do as he liked, Jehoiakim stopped paying them tribute and once again allied himself with the Egyptians. But remember, “An alliance with a powerful person is never safe,” because—as you may remember from last week—there’s always someone looking to be king of the mountain.

When Jehoiakim stopped paying tribute to Nebuchadnezzar, the King of the Babylonians, returned and laid siege to Jerusalem. He conquered the city, killed Johoiakm, took some Israelites into captivity, and installed a new king. If you think Jehoiakim wasn’t all that bright, meet Zedekiah.

Like Jehoiakim, Zedekiah played along with the Babylonians, but after ten years, it became increasingly clear that he wanted to stop paying tribute. Many were with him, but others, including that nagging prophet, Jeremiah, opposed.

Jeremiah told the people that the Babylonians were essentially the hand of God, working God’s judgment against them for their sins. As a visual aid, the Lord said to Jeremiah, “Make yourself straps and yoke-bars, and put them on your neck.” (Jeremiah 27:2) The yoke said to the people, “For a time, this must be you. You must be under the yoke of the Babylonians while God exacts His punishment on you for your misdeeds.” Jeremiah said, to King Zedekiah, “Bring your necks under the yoke of the king of Babylon, and serve him and his people and live.” (Jeremiah 27:12) As hard as he tried, the king and the people opposed, and even some that claimed to be prophets were against him, one of which we heard about today, Hananiah.

Hananiah, claiming to speak for God, said, “I have broken the yoke of the king of Babylon. Within two years I will bring back to this place all the vessels of the Lord’s house, which Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, took away from this place and carried to Babylon.” (Jeremiah 28:3) Hananiah was calling the people to rebuke Nebuchadnezzar and the prophecies of Jeremiah and to believe that they would be free within two years. This is where our reading from today came in. In responding to him, Jeremiah said, “Amen! May the Lord do so; may the Lord make the words that you have prophesied come true.” Jeremiah said, “Those are nice words, and I pray they come true.” Hananiah then broke the yoke that Jeremiah had fashioned for himself and declared that the yoke of Nebuchadnezzar would be broken similarly. Jeremiah heard these things and then went his way, and the people and King Zedekiah remained in their sin. Two months later, the prophet—the false prophet—Hananiah died, and the Babylonians completely sacked Jerusalem.

Thomas Sowell is an author, economist, and social commentator.

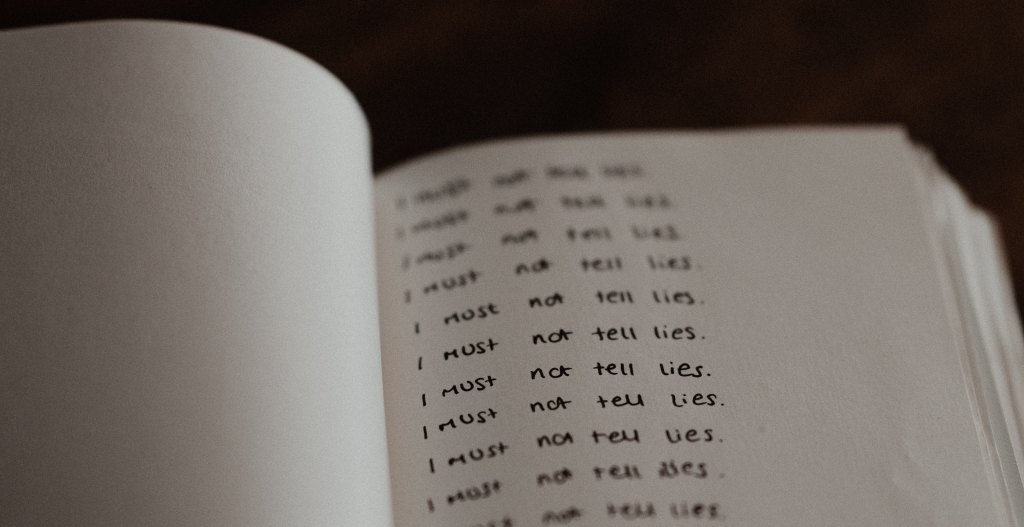

He wrote, “When you want to help people, you tell them the truth. When you want to help yourself, you tell them what they want to hear.” (The Thomas Sowell Reader, p.398) Jeremiah was speaking the truth, but Hananiah was simply telling the people what they wanted to hear. Like ol’ Boudreaux, Hananiah had told many lies, and he paid for his sin.

Jeremiah said, “As for the prophet who prophesies peace, when the word of that prophet comes true, then it will be known that the Lord has truly sent the prophet.” The Prophet who preached peace was Jesus. St. Paul tells us in his letter to the Ephesians that Jesus “came and preached peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near. For through him we both have access in one Spirit to the Father.” (Ephesians 2:17-18) And the peace that Jesus was preaching was not about the peace between nations, but the everlasting peace between God and His children—between God and us.

If that were the end, then all would be well, but throughout the New Testament, we hear of those who will come and spread lies like Hananiah. In his first Epistle, St. John tells us, “Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, for many false prophets have gone out into the world.” (1 John 4:1) Just so you know how bad these false prophets are, John declares they have “the spirit of the antichrist.” (1 John 4:3) St. Peter also warns us, “Be sober-minded; be watchful. Your adversary the devil prowls around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour.” (1 Peter 5:8) Jesus has prophesied and brought peace between God and humankind, it is ours for the asking. Still, some would seek to destroy that peace, so we must be on our guard against them. It can, however, get a little tricky. Why?

Paul wrote to Timothy, “The time is coming when people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their passions, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander off into myths.” (2 Timothy 4:3-4) Like Hananiah, these false prophets will tell us what we want to hear instead of what we need to hear. The heart of the false message is the same as it has always been. The same as it was in the beginning when the snake—the greatest of false prophets—tempted Eve and said things like, “Did God really say…” and “You will not surely die.” The false prophet’s message is confusing, for it contains half-truths and subtle lies, but they are there, and many believe.

So there are various false prophets in the world, and there is the snake, but there is one other false prophet that runs a close second to it. My friend, Stephen King, said it best, “We lie best when we lie to ourselves.” (It, p.445)

If we pay attention and stay true to the teachings of the Gospel, then I believe we have a good chance of not falling prey to the Hananiahs of the world, but when it comes to lying to ourselves, we are experts. We know all our own arguments and weaknesses, and strategies and the Hananiah within can play us like a fiddle. St. John told us to “test the spirits to see whether they are from God,” so we must also test our own spirit and those things we believe to be true. Are we simply telling ourselves those things we want to believe, or are they consistent with the teachings of Jesus? If we are lying to ourselves, then we’ve already lost. As The Bard wrote:

“This above all: to thine own self be true,

And it must follow, as the night the day,

Thou canst not then be false to any man.”

(Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 3)

Jesus said, “If you abide in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” (John 8:31-32) You are Jesus’ disciples. Do not listen to or tolerate the lies from outside yourself or from within, but seek to discern the truth.

Let us pray: O Mary, Mother of Mercy, watch over all people that the Cross of Christ may not be emptied of its power, that humankind may not stray from the path of the good or become blind to sin, but may put their hope ever more fully in God who is “rich in mercy.” May we carry out the good works prepared by God beforehand and so live completely “for the praise of his glory.” Amen.